[Edit: These first two paragraphs were added August 3, 2021, on the occasion of publication by Human Defense Initiative:

Today the foremost topical issue on the minds of the US pro-life world is the survival or demise of the Hyde amendment. US pro-life leaders are engaged, with one voice, in moral appeals to the obviously-deaf ears of the Democratic Party proponents and supporters of legislation that would have the effect of killing the Hyde Amendment, likely permanently. It should be obvious by now that these moral appeals will not work and may be little more than an exercise in feeling good. They will not work because the proponents of the legislation understandably perceive that while the US pro-life leadership may do some grumbling and whining, once the legislation is enacted and goes into effect, that leadership and all US pro-lifers will passively acquiesce in paying those lethal taxes – i.e., they will acquiesce in becoming parties to abortions and part of the abortion machinery. They will not resist paying the taxes. Becoming parties to abortions, they will lose their moral force, and the victory of the abortion juggernaut will be assured.

What would strike actual hesitancy, or even fear, in the hearts of the proponents of the legislation would be a pure moral flame in the form of a tax-resistance movement. They would fear it, because that principled tax revolt would be a black eye for Democratic Party rule, and because many people, in trying to understand that revolt, would think much more deeply about the reality of abortion than they had thought before – which could only benefit the pro-life side. So let pro-life leaders declare now their intention to organize such a movement if taxpayer funding of abortion is enacted. Some possible orientation is provided here.]

Michael Bowman’s conscience recoils at the idea of paying federal income tax, because some of it would go to Planned Parenthood. Federal funding of Planned Parenthood is not supposed to go for abortions, but Bowman, a software engineer who lives in Oregon, says that the $500 million dollar annual amount funds “knives, scalpels, [operating] rooms . . .,” etc. Moreover, whether or not he has mentioned it, federal funds do go directly for abortion in cases of rape and incest. Hence to pay taxes is to be complicit.

(Even if tax money did not actually help facilitate abortions, one might well find it morally repugnant to fund an organization that symbolizes, whitewashes, and misrepresents abortion, and one might object on those grounds. But Bowman has not expressly made that particular argument.)

Some would reply to Bowman that taxes are inevitable, that their various uses cannot please everybody, that they are a price of living in society, and that therefore taxpayers are absolved of any responsibility. To that thinking he responds:

The United States Federal Government and state governments are not responsible for keeping the conscience of its citizens “clean and intact.” That duty falls to the individual, there is no shifting of responsibility from the individual to the government. A Citizen cannot say “The Government made me do it!”

In the end we are all responsible for our own lives, souls and consciences, and our Founding Fathers knew this. This is why they elected to keep government in a small box, and to keep the power in the hands of the individual; so that the individual could live in a manner which did not cripple his conscience, or force him to surrender his soul to a small group of people in government that have their own agenda for power! *

To show the absurdity of thinking that the government can bear our moral responsibilities, Bowman sometimes asks listeners to imagine some of the hideous atrocities the government might order us to commit if we started to accept that it really does have the right to order us. Bowman wishes people to understand that if our government can force those who abhor abortions to participate in them, it can force its people to do anything. Eventually it becomes clear that citizen obedience of that kind is unacceptable and that we cannot escape from ourselves. Even for many who do not share all of Bowman’s small-government philosophy, his “there is no shifting of responsibility” will strike a chord. Liberals who have shared that latter idea have a long history of conscientious objection on different issues. Whatever powers we may want to give the government and whatever technical resources we may think should be at its command, it will never have the power to make us feel right when we have done wrong.

But what if the government of the land we live in falls into hands that do in fact order us to violate our consciences? Bowman’s above statement doesn’t say, but he has answered that question in his actions. He has not paid federal income tax since 1999.

Bowman was indicted for tax evasion in February 2017. But as the National Review has related, the law under which he was charged defines “evasion” only in terms of concealment of income or other intentional deception, whereas Bowman had been transparent about what he was doing. In April 2018 Judge Mosman of the U.S. District Court in Oregon dismissed the felony evasion charge. However, the prosecutors could still seek a new indictment. [Edit: Bowman has now said that the government has dropped the felony charges permanently.]

A more immediate issue for Bowman is four misdemeanor counts of willful failure to file tax returns, for which he was charged at the same time as the felony charge. Each of those counts could carry a sentence of a year in jail. However, he writes that he expects to win, because “I asked them for accommodation almost 20 years ago, and they failed to comply with federal law.” The trial is scheduled to start this August, and may see a big turnout of pro-life demonstrators.

Is Bowman completely alone in resisting taxes for the reason he did? In covering his April 2018 trial, The Oregonian noted: “[Kenneth] Medenbach . . . said he’s following Bowman’s lead, refusing to pay taxes, citing his own religious beliefs against abortion.”

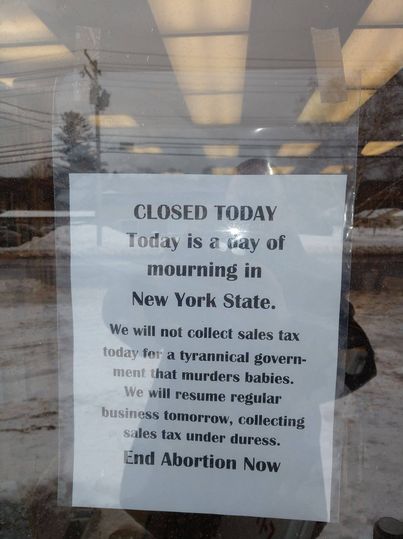

After the recent Cuomo-led institution of taxpayer funding of abortion in New York State, a bookstore owner named Jon Speed closed his store for one day in order to reduce, by a token amount, the sales-tax revenue available to the state.

Only Three out of 100 Million?

Out of about 100 million pro-lifers in the US, there must have been a few other instances, that I haven’t yet heard of, of tax resistance related to abortion. And of course pro-lifers are active in the legislative sphere in opposing taxpayer funding of abortion in the first place. But as regards dutifully paying federal income tax and state taxes that are already in place, essentially the pro-life response has consisted of total acquiescence. Moreover, some pro-lifers are aware that Facebook, Starbucks, Ben & Jerry’s, Microsoft, Paypal, General Electric, ExxonMobil, PepsiCo, United Airlines, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, etc., all donate or have donated to Planned Parenthood, and that if they use those companies, one effect will be to increase Planned Parenthood’s revenues. And yet there has been no organized boycott of those companies, even the ones that it would be almost painless for us to boycott. (As I write this, a boycott of Netflix is shaping up, though not because of funding. Let’s see if it goes anywhere.)

At this point we should make it clear that Bowman himself just wants to live his life as a free individual with a clean conscience. He chose not to pay taxes not with the purpose of starting a movement, but simply because he found his conscience to allow him, as an individual, no alternative. If there is any message he would like to send, it is not that others should do as he did, but that we should all understand the Constitutional limitations of government power in the land that we live in. And according to Bowman and his lawyers, those limitations in relation to the consciences and religious convictions of citizens are enshrined in Title 42, Chapter 21b of the United States Code, to be discussed below.

Yet though Bowman is not asking anyone to follow his example, what he says about conscience will inevitably make each pro-lifer ask themselves, “What about my conscience?” Joe Biden’s recent capitulation on the Hyde Amendment makes it clearer than ever that shortly after Jan. 20, 2021, big-scale federal tax funding of abortion might be the law of the land, and if pro-lifers seem ready to be walked over acquiescently in the event that it is, its proponents will be thinking “Why not?” Among some proponents, there may even be a component of wanting to break the spirit of pro-lifers.

There are three questions that pro-lifers will have to grapple with:

1. Is Bowman correct that payment of taxes is moral complicity in abortion? What about patronizing or using companies who support abortion?

2. Through what tax and other avenues does our money presently go for abortions?

3. If we are presently complicit, what options do we have regarding each of those avenues to rescue our consciences, and to do so in a way that will force other Americans to appreciate the strength of our convictions?

Let’s look at those three questions.

1. Is Bowman correct that payment of taxes is moral complicity in abortion? What about patronizing or using companies who support abortion?

If a prisoner in a concentration camp is ordered to kill a fellow prisoner or die oneself, then one should choose to die, clearly. On the face of it, to supply money, one of the essential cogs of the abortion machine, is to be no less instrumental in abortion than to use one’s hands to kill. But I have heard two main arguments against such an analogy:

a. Considering all the ways that your federal and state taxes will have to be spent, only a minuscule amount of it will ever go for abortion.

But the problem with this argument is that when we pay our taxes, we set an example. And once everyone pays, there will be thousands of abortions every year, in a big state like California, of babies who would otherwise have been spared.

b. As a pro-lifer wrote to me, “There’s probably something our taxes go to that would be morally objectionable to nearly every single person who pays taxes.” And yet if everyone withholds all tax money, we will lose much of the benefits that our Homo sapiens cooperation instinct could otherwise provide us for our mutual defense and our general welfare. Advanced civilization could not exist without a tax system involving mutual concessions.

This argument assumes that advanced civilization is of more value than preserving our innocence in relation to mass killing, an assumption that Bowman has attacked with effective reductio ad absurdum arguments. Moreover, I feel that civilization could in fact afford to accommodate refusal to pay taxes for a certain kind of reason. For more on this, see here. Let’s ask ourselves, if our tax money were being used to suction, poison, and dismember born children, would we acquiesce to that?

2. Through what tax and other avenues does our money presently go for abortions?

Even if we don’t pay income tax and don’t live in states with tax funding of abortion, probably all of us, through our spending habits and other actions that enrich people or companies in other states, do contribute to abortions, sometimes unknowingly, and in certain ways that are avoidable and other ways that are harder to avoid. For more on this, see here.

3. If we are presently complicit, what options do we have regarding each of those avenues to rescue our consciences, and to do so in a way that will force other Americans to appreciate the strength of our convictions?

As the link I provide under 2 makes clear, we cannot completely avoid leaving an abortion “footprint” on the earth in financial terms. But I would think that any pro-lifer would consider it their moral duty to minimize their footprint – their money that goes to abortion – at the cost of some degree of sacrifice of comfort and convenience for themselves. Preferably in a way that attracts attention to their strong convictions. Minimizing would begin with educating themselves as to where their money goes. I have tried to list the options for minimizing, some of them involving little sacrifice for a pro-lifer, some of them involving a lot, here.

Apart from what is incumbent on us for our own consciences, if we totally acquiesce in funding abortions but would not acquiesce in funding the killing of innocent born children, we send a message that we do not really believe an unborn child to have the moral value of a born child.

And incidentally, for the public to see a significant number of pro-lifers ready to make sacrifices, and to do so using an approach that cannot be painted as disturbing women, would go far toward burying some of the theories that pro-choice feminists often peddle as to what motivates pro-lifers.

One of the options, of course, is that chosen by Bowman. Let’s look again at his case. Basically under some circumstances, though not as it has worked out for him so far, such a case could hinge on Section 2000bb-1 of the United States Code. Bowman thinks that the courts and the IRS are afraid of opening the Title 42, Chapter 21b floodgates: its Section 2000bb-1 (Section 3 of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act), line (c) says, “A person whose religious exercise has been burdened in violation of this section may assert that violation as a claim or defense in a judicial proceeding and obtain appropriate relief against a government,” and according to (b) of that section, the government (not just the IRS) would have to demonstrate that funding Planned Parenthood with the money of a religious objector “(1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and (2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.” For more on this, see here.

On February 26 of this year, Bowman kindly spared me a little time on the phone, so that I could begin to fill in the partial picture of his adventures and thoughts that I had already gleaned from the media. Some of what I learned on that occasion is at the foregoing link. On that occasion Bowman also shared a wry observation on present-day political realities, saying that if the US government forced taxpayers to pay for erecting costly Jesus statues everywhere, then even though erecting those statues would not kill anyone and abortions do, we might see an outcry against compelled taxation for statues, and support for the idea that objectors should be accommodated, greater than is presently caused by the deaths of unborn children.

I mentioned above my belief that pro-lifers should be ready to embrace some degree of sacrifice to minimize their abortion footprint. Bowman is pro-life, but not in the most common sense of the term, because he does not advocate making abortion illegal. (He says only that abortion is between a woman and God and the woman’s conscience, and that if she aborts, he does not want to be a part of it.) Yet he sees the hideousness of abortion as much as any pro-lifer, and to avoid being a part of it, the sacrifice that he has been ready to make has been a big one. He was and is ready to go to jail.

I have not had the chance to meet Michael Bowman personally, and I do not know anything about him except data closely related to his fight with the IRS. I don’t know whether we should try to make him a poster child for the pro-life movement, and he makes it clear that he would not want to be. What he has undeniably contributed with his show of guts, however, is to throw a key moral and legal issue into clear relief for us, and it’s up to us to take it from there. Those who want to discuss this, let’s please meet on this Facebook page.

* Email of 31 March 2019.

© 2019

August 6, 2021 update:

Above we wrote, “The trial is scheduled to start on August 12 [2019] in Portland . . .” That trial ended on August 16. It ended in a hung jury, to the surprise of legal experts, who had considered it an open-and-shut case for the prosecution. During the trial, the judge (the same judge who had dismissed the felony case) had allowed Bowman “to raise what’s called a ‘good faith’ defense that he believed the government owed him an accommodation based on his reading of the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the Oregon Constitution.” The judge immediately declared a mistrial, and six days later he phoned the lawyers on both sides and “signaled that in a retrial he wouldn’t allow Bowman to raise” that defense. (See “After mistrial, judge says he made mistake in allowing man to argue religious objection to filing tax returns.”)

Believing that that flip-flop gave them no chance of avoiding conviction in the retrial, Bowman and his lawyer decided not even to contest, but instead to appeal and hope for better treatment in a higher court. Accordingly, Bowman was convicted in the Dec. 9, 2019 retrial, and immediately appealed, and remained free pending sentencing. His sentencing finally came on Aug. 20, 2020: four years’ probation (though technically he could have received four years in prison, and the prosecution had asked for fourteen months in prison). The judge “also ordered Bowman to pay $138,026 in restitution . . .”

The first hearing in the appeal trial has not been scheduled yet.

You may leave a reply, if you wish, without giving your name or email address. If you do give your email address, it will not be published. Back up your work as you type, in case of accidents.

See also “Bowman Wins Near-Total Legal Victory. Now the Pro-Life World Is on Trial Morally.”