I may expand on this later.

Robin Marty, a pro-choice activist, has covered the recent March for Life here.

The article surprised pro-lifers with its relative fairness. Though not neglecting to make a couple of criticisms of it, Kelsey Hazzard of Secular Pro-Life wrote, “But on the whole it was a much fairer piece than we would have gotten from any other pro-choice writer.” I don’t doubt that this is true.

However, let’s look at an important theme of the article. At one point Marty quotes Jill Stanek as saying, “Well, of course we want to get into the mainstream,” and Stanek’s son-in-law Andy Moore as saying, “We’d be more than happy to keep separate.” But there’s something strange about this. For one thing, Marty doesn’t quote Moore as using the word “mainstream.” Is Marty sure that he was referring to the mainstream — and not meaning, for example, “We’d be more than happy to keep separate from pro-choicers”? There is a difference between a dislike of socializing with some people, and being out of the mainstream. Wouldn’t a reluctance to be in the mainstream mean that one does not even want one’s policy views to prevail?

And regarding what Stanek said, well, with most Americans favoring some abortion restrictions, aren’t pro-lifers in the mainstream, which would also place their leadership in the mainstream? I wonder if Stanek said “mainstream media” rather than “mainstream.”

Stanek has tweeted regarding this, “I don’t remember what I said or the exact context of the sentence that came b4.”

If I understand correctly, by “sentence that came b4” Stanek is referring to Marty’s: “I had told [Stanek] that the part that stuck out to me most was this idea of an alternative culture that could stand as a complete counterpart to the world the rest of us interacted in, creating its own reality that anti-abortion and especially Christian conservative true believers could exist in, untouched.”

The main interpretive theme of the article, running alongside its fascinating factual coverage of the March, seems to be that pro-life activists are younger and more numerous and more well-intentioned, and even more joyous, than Marty expected, but that nevertheless they are out of touch with reality.

A willingness to take a fresh look is unusual in public discourse, and praiseworthy. But what about the concept that pro-life activists are out of the mainstream and that some of them don’t even want to be in it?

A serious minority party or movement is usually said to be “the opposition,” but not out of the mainstream. Activists for any cause are always in a minority, but if the cause itself is popular, do we say that the activists are out of the mainstream? Those who actually marched for civil rights in Washington in 1963 were in a small minority in the US, but were they in a “bubble”?

Marty tries to support her “bubble” idea by noting that “The ‘us versus the rest of the world’ theme was consistent through the panels I attended.” But surely that is a fairly common denominator of all struggles against oppression, and pro-lifers feel that their unborn sisters and brothers are oppressed.

So the best way to make sense of the idea that pro-life activists are out of the mainstream (and that some of them don’t even want to be in it) is to infer that to Marty, their being out of the mainstream does not reflect on their numbers or their seriousness about changing policy, but rather is synonymous with their “creating [their] own reality” where their ideas will not be threatened.

And what is the real reality that, to Marty, pro-life activists are out of touch with? It is that an unborn child is a “life,” whereas its mother is a “person”: I will never, ever believe that the rights of a life developing in the womb outweigh the rights of the person carrying it, or that she has an obligation once pregnant to provide society with a live, full-term infant regardless of her own emotional or medical needs. (Which also seems to echo the occasionally-heard conspiracy theory that pro-lifers are motivated by a desire to increase population.)

The “reality” that an unborn child is not a person is of course almost the main crux of the abortion issue and is normally admitted by both sides to be highly subjective. In another post, I looked at it this way:

In thinking of the unborn, some people tend to perceive a still picture, an organism frozen in time, while some tend to perceive a process. If you kill a small clump of cells lacking, perhaps, even a beating heart, is it correct to say that you are killing an organism whose life presently has little value, or to say that you are depriving it of the complete human life which has started as a process? In fact, both statements are correct. Obviously the perception of a process is a more complete perception. If one does perceive a process, then one will also intuit that the unborn is a full-fledged member of human society, and will call it a person. But there is no way to prove logically that the process model is more valid morally than the frozen-in-time model as a basis for deciding the fate of the organism. . . . I would call the “process” perception of the unborn holistic, and would call the frozen-in-time perception reductive or mechanistic; but scientifically, neither is incorrect . . .

For some comments by pro-lifers on Marty’s article, see Secular Pro-Life’s Facebook status of February 1 at 9:24pm.

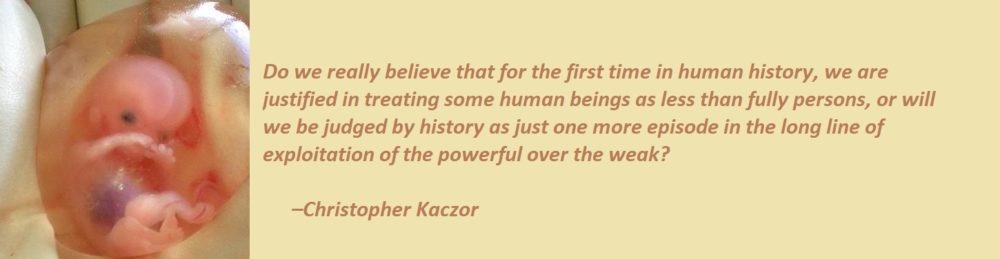

By the way, here is the one photo that to me best captures the big array of feelings that drive the March for Life.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens could change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has!” (Margaret Mead)

© 2015

You may leave a reply, if you wish, without giving your name or email address. If you do give your email address, it will not be published. Back up your work as you type, in case of accidents.

Some future posts:

Life Panels

Evolution, and the Humanizing and Uplifting Effect on Society of a Commitment to the Unborn

A Trade-Off of a Sensitive Nature

Unborn Child-Protection Legislation, the Moral Health of Society, and the Role of the American Democratic Party

The Motivations of Aborting Parents

Why Remorse Comes too Late

The Kitchen-Ingredients Week-After Pill

Unwanted Babies and Overpopulation

The Woman as Slave?

Abortion and the Map of the World